Chocolate Source: Ecuador

I recently had the opportunity to go to Ecuador to source chocolate couverture and see the process first-hand from tree- and seed-to-bar. No, that is not a mistake, cocoa bean is actually a misnomer, and the part of the cacao plant that we use to make the deliciousness that we call chocolate is the seed. We’ve been using the term bean in regular parlance for years, so I’ll use the two interchangeably as I give you a condensed tour of what I saw and tasted while visiting cacao forest plantations and processing facilities in Ecuador.

Behold: chocolate! Yes people, this is what chocolate looks like as it grows and ripens on the tree. You are looking at a cacao pod of the Arriba Nacional varietal, a rare type of heirloom cacao indigenous to Ecuador with a distinctive flavor. The Arriba Nacional is a lower yield type that is susceptible to diseases that have become more common with global warming, and has in past years become rare because it has made more economic sense for cacao farmers to cut down these trees and plant a more hardy, higher yielding hybrid in its place. This means losing a lot of flavor in the process as well as a lot of history, and according to many Ecuadorians, a piece of national identity.

Cacao farmers are preserving these valuable plants by removing diseased fruit and disposing of it so it doesn’t infect other plants, as well as cutting affected branches and grafting new ones onto old-growth trees, thus preserving yield and keeping the tree and its neighbors healthy.

Let’s back up a little and go back to the very beginning of a cacao seed’s life. These delicate flowers, about the size of an American dime, are cacao blossoms, scattered up and down the trunk of these incredible old-growth trees. The trees I visited grow in a natural, shaded forest environment with other South American species like rubber trees, kapok and sometimes introduced introduced species from Southeast Asia like Tagwa and Bamboo, as well as lots of critters including robust colonies of ants and other insects, birds, and monkeys.

When the cacao pod is ripe, they are cut from the tree with a swift swipe of a machete and cut open to reveal the fleshy, somewhat slimy fruit inside, covering and holding together rows of seeds.

The white flesh, called baba, is fruity and fresh in flavor, with a slight and pleasing acidity, delicious and delicately aromatic. I would drink this juiced, it’s refreshing as is! It’s also an important component in the next step of cacao processing, fermentation.

The chocolate seeds, freshly scraped from the pods and still encased in the fruity baba, are transported to fermentation bins. Piled inside and covered, things start heating up. The fermentation process starts to naturally heat the beans and transform them through chemical reactions thanks to naturally occurring enzymes in the fruit.

The smell is palpable, pleasingly pungent, vinegar-y, earthy and musty. The seeds are fermented for at least four days, here using an ingenious terraced method of moving seeds that have gone through the first part of the process to the next bin below, so new seeds can be put into the topmost bin to start the process.

Once the beans have fermented, they are dried in the sun, often on a concrete patio. Here, they begin the drying process on a raised palette made from split bamboo so they dry more efficiently, shuffling through the beans row-by-row to turn them and further ensure they are dried evenly.

The beans drying on the patio are raked regularly to turn them and ensure even drying.

These fermented and dried beans, after being hand sorted for defects and twigs and any other materials that might have gotten mixed in, are ready to make the trip to the processing factory where they will be graded, roasted, winnowed and ground to become the delicious chocolate we know and love!

Some growers have formed farmer-owned cooperatives, pooling resources and knowledge to grow high-quality beans, and are therefore able to command higher prices for their work, selling their beans directly to a processor in-country, aka direct trade. When the beans arrive at the processing factory they are checked for quality and defects. These ingenious little devices are made to place a random sampling of beans inside the individual notches on one side of the tray, snapping the tray case shut and then slicing them in half by inserting a sharp guillotine. The beans can then be thoroughly inspected, and if they are not up to muster they are refused, ensuring the quality of those that pass inspection to be made into the highest grade couverture and chocolate bars.

Next comes the roasting process, when the beans start to smell chocolate-y as we know it. Some of the steps and processes are similar to coffee production, an agricultural product that grows in the same regions as cacao.

Roasted beans are cracked so the interior kernel, the nib, is ready to be winnowed to remove the outer husks and ground into smooth, glorious cocoa liquor (not alcoholic, just the term for pure, liquid chocolate). Chocolate is then further refined/conched in a melangeur, stone-ground with any added ingredients like cocoa butter (also from cocoa beans and a chocolate product), sugar, and if you’re making milk chocolate, dried milk solids.

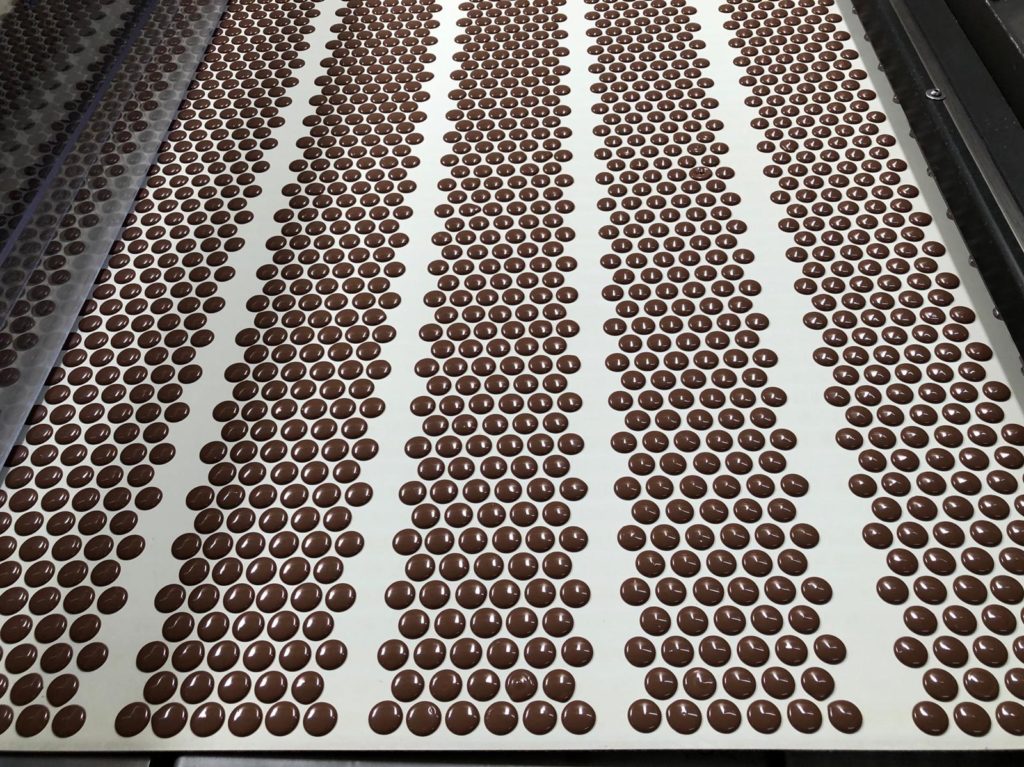

The resulting ground and liquid chocolate is formed into blocks, bars or pastilles at this point, and ready for chocolatiers like us to use in our confectionery recipes.

Many thanks to Republica del Cacao, the tree- and bean-to-bar origin-made chocolate company that led me and a small group of incredible chocolatiers and pastry chefs through the whole process, including a swoon-worthy tasting at the end. I feel so fortunate to have seen the process behind making one of my favorite foods through the generosity of the expert farmers, harvesters, processors and chocolate makers in Ecuador who showed us their craft. This chocolate is nuanced, complex, flavorful and full of passion, our kind of chocolate, which we get to share with you.